LIVR – Data Validation Without Any Issues

Each programmer must have come across the necessity to check user’s input a number of times. Having a 12-year experience in web development, I have tried my hands at dozens of libraries but didn’t manage to find the one to handle all my tasks.

Common issues with data validation libraries

Issue #1. Most validators check only the data having the described checking rules. It’s crucial for me that each obviously forbidden user’s input is ignored. Meaning that the validator must cut all the data for which the validation rules aren’t defined. It is a fundamental requirement.

Issue #2. Procedural description of the validation rules. I don’t want to think about the validation algorithm every time; I just want to describe declaratively how the proper data must look. Basically, I want to set a data scheme (will explain at the end of the post why not the “JSON Schema”).

Issue #3. Description of the validation rules in code. It doesn’t seem all that problematic at first, but it terminates all the chances of successful validation rules serialization and using of the same validation rules both in backend & frontend.

Issue #4. The validation stops at the first field with an error. This approach doesn’t allow highlighting all the faulty/necessary fields in a form at once.

Issue #5. Non-standardized error messages. For instance, “Field name is required”. I can’t show a user such an error because of the following reasons:

- A field can have completely different name in the interface

- The interface isn’t necessarily in English

- An error type must be distinguished. E.g., errors of a blank value can be displayed in a special manner

What I mean to say is that not the ordinary error messages but the standardized error codes must be returned.

Issue #6. Numeric error codes. These are just poorly adapted for use. I want the error codes to be intuitive. Don’t you agree that the error code “REQUIRED” is much more comprehensible than a code “27”? The logic here is similar to one applied when working with exception classes.

Issue #7. There is no possibility to check the hierarchical data structures. Such a possibility is a must nowadays, in the times of JSON API & stuff. In addition to the hierarchical data validation itself, a return of the error codes for each field must be provided.

Issue #8. A limited set of rules. The standard rules are never enough. The validator must be extensible and susceptible to an addition of the rules of any complexity.

Issue #9. Too wide a range of responsibilities. The validator mustn’t generate forms, it mustn’t generate code; it mustn’t do anything except the validation.

Issue #10. Inability to conduct an additional data processing. Practically in any case, when there is validation, there is also a necessity of some kind (oftentimes preliminary) of an additional data processing: cutting the forbidden symbols, converting text into lowercase, deleting excessive spaces. It’s especially relevant to delete the spaces at the beginning and the end of the line. They don’t belong there in 99% of cases. I know that I’ve already said that the validator mustn’t do anything except the validation.

5 years ago, a decision was made to develop a validator which would be free of all the above-mentioned problems. Thus, LIVR (Language Independent Validation Rules) came to be. There are Perl, PHP, JavaScript, Erlang, Java, Python, Ruby implementations. The validator has been used in the production for lot of years, practically in each & every project of a company. The validator works both on a server and directly on a client’s machine. You can play around with it here – webbylab.github.io/livr-playground/

The key concept was that the validator’s core must be minimal and all the validation logic must be located in the rules (in their implementation, to be exact). Meaning that there is no difference between the “required” (checks the availability of a value), “max_length” (checks the maximum length), “to_lc” (converts data into lowercase), and “list_of_objects” (helps to describe the rules for a field which includes an array of objects) rules.

In other words, the validator doesn’t know anything about:

- Error codes,

- The fact that it’s able to validate hierarchical objects,

- The fact that it’s able to transform/clean data,

- Much more.

All this is a responsibility of the validation rules.

LIVR specifications

Since the task was set to create a validator independent of a programming language (some kind of a mustache/handlebars stuff) but within the data validation sphere, we started with the composition of specifications.

The specifications’ objectives are:

- To standardize the data description format.

- To describe a minimal set of the validation rules that must be supported by every implementation.

- To standardize error codes.

- To be a single basic documentation for all the implementations.

- To feature a set of testing data that allows checking if the implementation fits the specifications.

- The specifications are available on livr-spec.org

- The basic idea was that the description of the validation rules must look like a data scheme and be as similar to data as possible, but with rules instead of values.

The example of the validation rules description for an authorization form:

{

email: ['required', 'email'],

password: 'required'

}The example of the validation rules for a registration form (demo):

{

name: 'required',

email: ['required', 'email'],

gender: { one_of: ['male', 'female'] },

phone: {max_length: 10},

password: ['required', {min_length: 10} ]

password2: { equal_to_field: 'password' }

}The example of an attached object’s validation:

{

name: 'required',

phone: {max_length: 10},

address: { 'nested_object': {

city: 'required',

zip: ['required', 'positive_integer']

}}

}Validation rules

In what manner the validation rules are described? Each rule consists of a name and arguments (very similar to function calls) and, commonly, is described by the following manner {“RULE_NAME”: ARRAY_OF_ARGUMENTS}. An array of rules (which are applied in the subsequent order) is described for each field.

For example,

{

"login": [ { length_between: [ 5, 10 ] } ]

}i.e. we have a “login” field and a “length_between” rule which includes 2 arguments (“5” & “10”). This is the example of the fullest form, but the following simplifications are permitted:

- If there is a single rule for a field, an array is unnecessary;

- If a rule includes one argument, then only that one argument can be passed (without the need to embed it into an array);

- If a rule doesn’t include any arguments, then only the rule’s name can be put down.

All three formats are identical in nature:

"login": [ { required: [] } ]

"login": [ "required" ]

"login": "required"It is described in more details in the specifications’ chapter “How it works”.

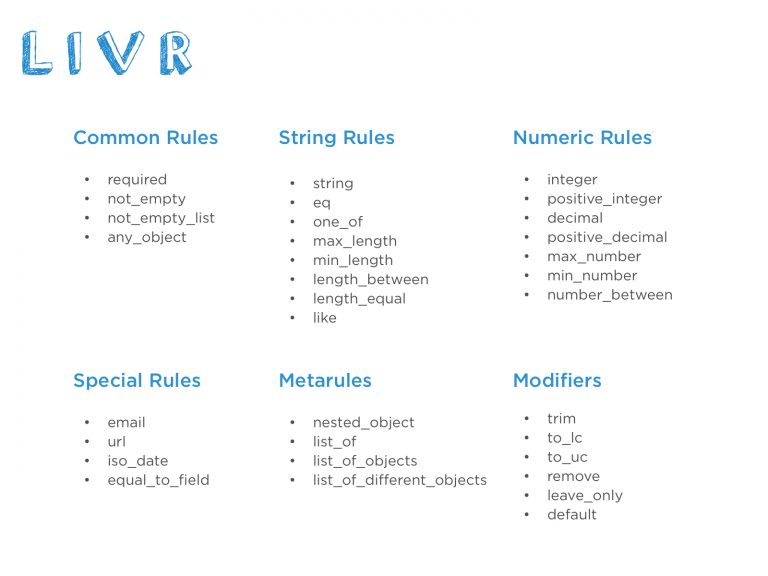

Supported rules

All the rules can be divided into 3 global groups:

- The rules that validate data (numbers, lines, etc.), e.g. “max_length”.

- The rules that allow composing more complex rules out of the simple ones, e.g. “nested_object”.

- The rules that transform the data. E.g. “to_lc” but the validator itself doesn’t make any difference between them, they’re all equal in rights for it.

Here’s a general list of the rules that must be supported by each of the validator’s implementation:

Common rules

- required – a field is necessary & a value mustn’t be empty;

- not_empty – a field is unnecessary but if it’s there, it can’t be empty;

- not_empty_list – a value must include a massive which isn’t empty;

- any_object – checks that the value is a plain object.

Rules for checking lines

- one_of

- max_length

- min_length

- length_between

- length_equal

- like

- string

- eq

Rules for checking numbers

- integer

- positive_integer

- decimal

- positive_decimal

- max_number

- min-number

- number_between

Rules for special formats

- url

- iso_date

- equal_to_field

Rules for description of more complex rules (metarules)

- nested_object – describes the rules for a nested object;

- list_of – describes the rules each list element must correspond with;

- list_of_objects – a value must be a massive of objects of a required format;

- list_of_different_objects – use it when you need to check the massive of the various types of objects;

- variable_object – allows you to describe validation rules for field that can contain different objects;

- or – the rule takes sets of other rules and applies them one after another until successful validation.

Rules for data transformation (the names start with a verb)

- trim – removes spaces in the beginning & the end;

- to_lc – converts into lowercase;

- to_uc – converts into uppercase;

- remove – removes chosen symbols;

- leave_only – leaves only the chosen symbols;

- default – sets value if it is not present.

Metarules

The examples & error codes for each rule can be found in the LIVR specifications. Let’s only discuss the metarules in more details. The metarules are the rules that allow combining & transforming the simple rules into the more complex ones for complex hierarchical data structures’ validation. It’s important to understand that the validator doesn’t make any difference between the simple rules and the metarules. The metarules are identical to the mentioned before “required” (yes, I am repeating myself).

nested_object

Allows describing the validation rules for the nested objects. You will use this rule very often.

The error code depends on the nested rules. If a nested object isn’t a hash (dictionary), a field will contain the following error: “FORMAT_ERROR”.

The usage example (demo):

address: { 'nested_object': {

city: 'required',

zip: ['required', 'positive_integer']

}}List_of

Allows describing the validation rules for a list of values. Each rule will be applied to each element of the list. The error code depends on the nested rules.

The usage example (demo):

{ product_ids: { 'list_of': [ 'required', 'positive_integer'] }}List of objects

Allows describing the validation rules for an array of hashes (dictionaries). It is similar to the “nested_object” but always awaits the array of objects. The rules are applied to each element in the array.

The error code depends on the nested rules. In the case when a value isn’t an array, a “FORMAT_ERROR” code will be returned for a field.

The usage example:

products: ['required', { 'list_of_objects': {

product_id: ['required','positive_integer'],

quantity: ['required', 'positive_integer']

}}]List of different objects

It is identical to the “list_of_objects”, but there are cases when an array contains the objects of various types. The object’s type can be defined by a special field, e.g. “type”. The “list_of_different_objects” allows describing the rules for a list of objects of a various types.

The error code depends on the nested validation rules. If a nested object isn’t a hash, the field will include the “FORMAT_ERROR” error.

The usage example:

{

products: ['required', { 'list_of_different_objects': [

product_type, {

material: {

product_type: 'required',

material_id: ['required', 'positive_integer'],

quantity: ['required', {'min_number': 1} ],

warehouse_id: 'positive_integer'

},

service: {

product_type: 'required',

name: ['required', {'max_length': 20} ]

}

}

]}]

}In this example, the validator will check “product_type” in each hash and use the respective validation rules according to the field’s value.

Format of errors

As I’ve already mentioned, the rules return the inline error codes comprehensible to any developer, e.g. “REQUIRED”, “WRONG_EMAIL”, “WRONG_DATE”, etc. Now, the developer can understand where exactly the error has occurred; all that’s left is to accessibly explain in which lines it’s occurred. In order to do that, the validator returns a structure identical to the one it received for a validating purpose, but it includes only the lines with errors & inline error codes instead of initial values in the fields.

For instance, there are the validation rules:

{

name: 'required',

phone: {max_length: 10},

address: { 'nested_object': {

city: 'required',

zip: ['required', 'positive_integer']

}}

}and the validation data:

{

phone: 12345678901,

address: {

city: 'NYC'

}

}eventually, we get the following error

{

"name": "REQUIRED",

"phone": "TOO_LONG",

"address": {

"zip": "REQUIRED"

}

}REST API & errors format

The return of the comprehensive error messages always requires developers’ extra effort. There’s only few REST APIs that provide a detailed info in error messages. It usually comes as far as “Bad request”. Seeing the error’s related field and the field’s name isn’t enough as data can be hierarchical and include the array of objects. In our company, we handle such moments the following way – we describe the validation rules via the LIVR for each & every request. In the case of the validation error, we return the error’s object to a client. The error’s object includes the error’s global code and an error received from the LIVR validator.

For instance, you’re passing data to a server:

{

"email": "user_at_mail_com",

"age": 10,

"address": {

"country": "USO"

}

}you get this as an answer (validation demo on livr playground):

{"error": {

"code": "FORMAT_ERROR",

"fields": {

"email": "WRONG_EMAIL",

"age": "TOO_LOW",

"fname": "REQUIRED",

"lname": "REQUIRED",

"address": {

"country": "NOT_ALLOWED_VALUE",

"city": "REQUIRED",

"zip": "REQUIRED"

}

}

}}This is much more informative than just “Bad request”.

Working with aliases and registering custom rules

The specifications includes only the most commonly used rules, but each project has its own specifics and, oftentimes, there occur such situations where some or other rules are lacking. Considering that, one of the key requirements for the validator initially, was an ability of its extension with the custom rules of any type. Initially, each implementation had its own rules’ description mechanism. However, starting from the version 0.4 of the specifications, we have introduced a standard way of creating the rules based on the other rules (creation of aliases), which covers 70% of the situations. Let’s review both options.

Creation of an alias

The way the alias is registered depends on the implementation, but the way the alias is described is regulated by the specifications. Such approach allows, for example, to serialize the aliases’ descriptions and use them within various other implementations (e.g. within the Perl-backend & JavaScript-frontend).

// Registering аlias "valid_address"

validator. registerAliasedRule({

name: 'valid_address',

rules: { nested_object: {

country: 'required',

city: 'required',

zip: 'positive_integer'

}}

});

// Registering аlias "adult_age"

validator.registerAliasedRule( {

name: 'adult_age',

rules: [ 'positive_integer', { min_number: 18 } ]

});// Now aliases are accessible as common rules.

{

name: 'required',

age: ['required', 'adult_age' ],

address: ['required', 'valid_address']

}Furthermore, one is able to set up their own error codes for the rules.

For instance,

validator.registerAliasedRule({

name: 'valid_address',

rules: { nested_object: {

country: 'required',

city: 'required',

zip: 'positive_integer'

}},

error: 'WRONG_ADDRESS'

});and in the case of the address validation error, we are to get the following message:

{

address: 'WRONG_ADDRESS'

}Registering fully-featured rule on the example of JavaScript implementation

The callback functions, which do the checking of values, are used for the validation. Let’s try to describe a new rule called “strong_password”. We will check the values to consist of over 8 characters and include digits & letters in upper & lowercase.

var LIVR = require('livr');

var rules = {password: ['required', 'strong_password']};

var validator = new LIVR.Validator(rules);

validator.registerRules({

strong_password: function() {

return function(val) {

// We skip null values. To test the required value, we have the "required" rule.

if (val === undefined || val === null || val === '' ) return;

if ( length(val) < 8 || !val.match([0-9]) || !val.match([a-z] || !val.match([A-Z] ) ) {

return 'WEAK_PASSWORD';

}

return;

}

}

});Now, let’s add the ability to set the minimum number of characters in the password and register this rule as global (available in all the validator’s instances).

var LIVR = require('livr');

var rules = {password: ['required', {'strong_password': 10}]};

var validator = new LIVR.Validator(rules);

var strongPassword = function(minLength) {

if (!minLength) throw "[minLength] parameter required";

return function(val) {

// We skip null values. To test the required value, we have the "required" rule.

if (val === undefined || val === null || val === '' ) return;

if ( length(val) < minLength || !val.match([0-9]) || !val.match([a-z] || !val.match([A-Z] ) ) {

return 'WEAK_PASSWORD';

}

return;

}

};

LIVR.Validator.registerDefaultRules({ strong_password: strongPassword });In such manner, a quite simple one, the registration of the new rules occurs. If you need to describe the more complex rules, it would be best to look through the list of standard rules implemented in the validator:

- Common

- Numeric

- String

- Special

- Metarules

- Modifiers

There is a possibility to register the rules that would not only validate the value but also modify it. For example, convert into uppercase or delete extra spaces.

What to do if I want to create own implementation of the LIVR validator?

If you wish to make your own implementation of the validator, check out the set of test-cases, it was created in order to make things easier for you. If your implementation passes all the tests, it can be considered correct. The test suite consists of 4 groups:

- “positive” – positive tests for general rules;

- “negative” – negative tests for general rules;

- “aliases_positive” –positive tests for rules’ aliases;

- “aliases_negative” – negative tests for rules’ aliases.

Basically, each test includes several files:

- rules.json – description of the validation rules;

- input.json – structure passed to the validator for a check;

- output.json – cleared structure received after the validation.

Each negative test includes “errors.json” instead of “output.json” with the description of an error which must occur as a result of the validation. In the alias tests, there’s an “aliases.json” file with aliases that must be registered in advance.

Why not JSON Schema?

A quite frequently asked question. Briefly, there are a couple reasons:

- The complex format of rules. I’d want for the structure with rules to be as similar to the structure with data as possible. Try and describe this example through the JSON Schema.

- The format of errors isn’t specified & different implementations return the errors of different formats.

- There is no data transformation, e.g. “to_lc”.

JSON Schema includes interesting features, like an ability to set the maximum number of elements in the list. In the LIVR, however, that is implemented simply by adding one more rule.

LIVR links

- LIVR specifications (the latest version – 2.0)

- Test suite

- LIVR Playground

- LIVR Multi-Language Playground

- JavaScript implementation

- Perl implementation

- Perl6 implementation

- PHP implementation

- Java implementation

- Ruby implementation

- Erlang implementation (Olifer)

- Erlang implementation (Liver)

- Python implementation

- Article on LIVR & Perl implementation in the PragmaticPerl magazine

- Talk on LIVR 2.0 at the OSDN-UA 2017 conference

Written by:

Viktor Turskyi

Senior Software Engineer at Google Non-Executive Director and co-founder at WebbyLab.

More than 15 years of experience in the field of information technology. Did more than 40 talks at technical conferences. Strong back-end and fronted development background. Experience working with open-source projects and large codebases.

Rate this article !

26 ratingsAvg 4.6 / 5

Avg 4.5 / 5

Avg 4.5 / 5

Avg 4.4 / 5

Avg 4.6 / 5

Avg 4.6 / 5

Avg 4.7 / 5